“I am sorry to say that we decided against moving you to the next stage of the process, primarily for missing some essential tech skills”.

This was the email I received end of October 2020. It was the fourth rejection after spending a huge amount of time going through hiring processes, technical interviews, technical tests, and other joys. I didn’t understand what was happening: every company I worked with was happy about my work, my skills, and my involvement. As a professional developer for 10 years, I never had so many rejections in this short amount of time.

I already written how much I find technical tests useless, so I was naturally trying to explain these failures thanks to weird processes and random tests I never trained for. On top, nobody seemed to be interested in my side projects, this blog, my self-studies, and everything else I’m spending a crazy amount of time doing.

Still, a voice in my head was telling me that it was expected. “You knew this would happen”, it was whispering to me, “you always knew that you’re a cheater. A fraud. You can’t hide anymore”.

It was in the middle of the Covid pandemic, days after terrorist attacks in my native country and the implementation of a lockdown in the country where I was living. This email was more than I could handle. It led me to abandon all my side projects, this blog, and mostly everything else, for months.

Most of my thoughts were converging to this voice in my head. It wasn’t whispering anymore but screaming, pointing its finger at me. “You don’t deserve to be a developer. You’re not good enough. You’ll fail and you won’t learn. You’ve been coding for decades, all for nothing”.

I knew the imposter syndrome before, or at least I thought. I never would have imagined that this feeling could get that strong. It wasn’t rational, I knew it, but at the same time I couldn’t bring down this voice pushing me deeper and deeper into dark places.

Eventually, I tried to rationalize a bit more about what was happening in my head. I decided to do some research, to see the body of studies done on the topic, to understand why these feelings were poisoning my life. This led me to write this article.

More precisely, we’ll try to answer these questions:

- What’s the imposter syndrome?

- What are the symptoms of the imposter syndrome?

- What leads to the imposter syndrome?

- Can everybody be victim of the imposter syndrome?

- What are the consequences of the imposter syndrome?

- How to overcome the imposter syndrome?

We’re about to dive into our mental world.

What’s the Imposter Syndrome?

Studies About The Imposter Syndrome

Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes conducted in 1978 the first study about the imposter syndrome. It was written after conducting psychotherapies with over 150 highly successful women.

Following this study, Pauline Clance published in 1985 the book “The Impostor Phenomenon: Overcoming the Fear That Haunts Your Success”. These two pieces have been very influential on the subject, and they mark the beginning of the explosion of articles and studies about the imposter syndrome.

According to a recent study:

- Between March 2018 and March 2019, 2317 Internet articles were about the imposter syndrome.

- The imposter syndrome has been the result of 133 425 engagements on social media.

In this huge amount of information, only 284 studies have been pair reviewed, half of them published the last 6 years. This article will look at some of them.

If you do some research on the topic, you’ll notice that many studies use the terms “imposter phenomenon” instead of “imposter syndrome”. Don’t get confused: it’s the same thing. Other terms are sometimes also used: “impostorism” or “imposter fear”, for example. There are sometimes subtle differences between these concepts, but they’re mainly the same thing.

For simplicity, I’ll only use the terms “imposter syndrome” in this article.

Definition

What’s this imposter syndrome? Here’s the most complete definition I’ve found.

Experience of intellectual fraudulence despite measured success manifesting in denial of one’s competencies, fear of failure, perfectionism, and difficulty owning and enjoying success.

The imposter syndrome is not binary but more like a scale. Some people will feel the imposter syndrome creeping in their lives more often than others. The intensity of these feelings can be very different between individuals too.

To take an analogy I used in another article I’ve written about burnout, we can think of the imposter syndrome as a road you begin to walk on and, the more you’ll spend time on it, the more you’ll go into darker and darker places. Let’s call this road the imposter road.

The Symptoms of the Imposter Syndrome

Let’s now speak about Davina, your colleague developer. Davina has to cope with a strong imposter syndrome. What are the characteristics of her feelings?

The Six Characteristics

In her book, Pauline Clance defines 6 characteristics of the imposter syndrome:

- The imposter cycle.

- The need to be special or very best.

- The superman (or superwoman) aspect.

- The fear of failure.

- The denial of competence and discounting praise.

- The fear and guilt about success.

According to Pauline Clance, you need to have at least two of these characteristics to experience the imposter syndrome. Let’s review them in more details.

The Imposter Cycle

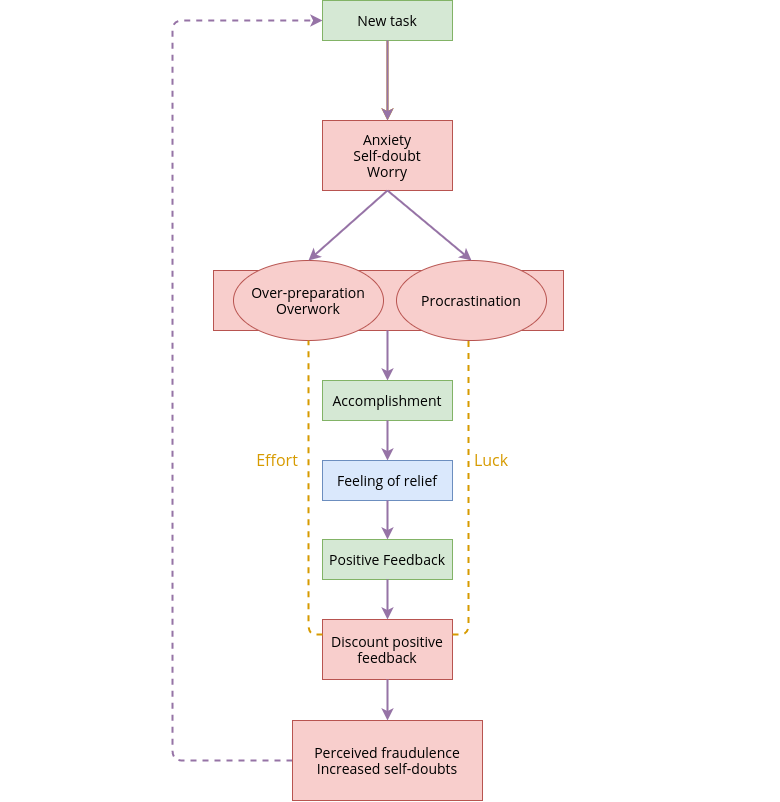

This is the most important characteristic of the imposter syndrome. The imposter cycle is not a virtuous one, but terribly vicious.

Davina, your colleague developer experiencing a strong imposter syndrome, has a tendency to overwork, get praise, and be happy about it. For a short time. Then, the imposter syndrome kicks in. At that point, her thoughts will look like this:

- “If my good results are due to hard work, it’s because I don’t have enough skills to do it easily.”

- “My good results are pure luck and not because I’m good in what I’m doing.”

- “My good results are not that good; my standards are higher and I didn’t reach them.”

- “I’ve succeeded because I knew what people were expecting, or because I used other manipulative techniques to obtain this result. Not because I’m good.”

These thoughts will cause a lot of anxiety for Davina. As a result, she’ll overwork even more, trying to hide her perceived fraudulence. What happens, then?

- More praise will come, Davina will reject them, and the cycle will repeat.

- Overworking might decrease the quality of her work. In that case, her colleagues will criticize her more and more, and she will have the impress to be discovered as the fraud she thinks she is.

The more Davina will spend time in the imposter cycle, the more she’ll move forward in the darkness of the imposter road. We’ll see the possible consequences later in this article.

Let’s illustrate this important idea more precisely (from this study):

The Need to be Special

As humans, we need to feel special.

Before going to the university, Davina was the first (or one of the first) at school. It gave her the impression that she was special compared to her peers. She was more intelligent. She was a high achiever. Every teacher was praising her good results. But when she entered a bigger setting, the university, she saw many others better than her.

The conclusion was logical: she wasn’t that good. Maybe she was not even good? What she believed was not true. She began to think, gradually, that she was a phony.

The Superman (or Superwomen) Aspect

Perfectionism can go hand in hand with the imposter syndrome.

Davina has very high standards almost impossible to reach. She wants to feel special, like she once felt. As a result, she became too perfectionist, overworking her way to success.

The Fear of Failure

Again a strong feeling which comes back pretty often nowadays.

As Davina was taught at school, failure was not acceptable. When her grade was low, it was a shame for her teachers, her friends, and her family.

Today, even if her Twitter was screaming feel-good messages praising failure as a necessary ingredient for success, she had difficulties to accept it. Many of her colleagues and friends didn’t accept it, either. Making a mistake at work or failing at an interview was proving to herself that she wasn’t good, even if some of her colleagues were praising her skills.

As a result, overworking looked like the only solution to be sure to avoid the horrible failures.

Denial of Competence and Discounting Praise

Davina has difficulties to accept praises as truth. For her, they are just the result of external factors independent of her control, not because she’s talented.

She created an inner narrative to prove to herself that she didn’t deserve these praises, and, at the end of the day, she was just an imposter trying to hide in order to keep her job.

Fear and Guilt About Success

Since Davina has many more praises than other colleagues, she feels the guilt of being different. She feels less connected with her peers. She feels alone.

Additionally, she’s afraid that people will expect even more from here than before because of these praises. For her, they might discover that she’s just a fraud! As a result, she’s uncertain to keep her actual level of performance, and she’s often reluctant to accept more difficult tasks or new responsibilities.

We often hear about the fear of failure nowadays, but the fear of success is, for many of us, as real and destructive.

The Neurotic Imposture

Another study From Harvey and Katz from 1985 (cited in Hellman & Caselman in 2004) proposed three core characteristics for the imposter syndrome:

- Believes that the others have been fooled to recognize good results.

- Fear of being exposed as an imposter.

- Inability to attribute one’s achievement to internal qualities such as ability, intelligence, or skills.

According to Harvey and Katz, the three characteristics are required to call yourself a victim of the imposter syndrome. That’s the only difference with Pauline Clance’s analysis of the problem.

Another study from Ketz de Vries in 2005 include a broader definition of the imposter syndrome, arguing that it’s something expected in a society, and therefore somehow normal.

We have tendencies to hide our weaknesses. We hide many aspects of our private self in a public setting. The fraudulent feeling can come from the impression of hiding who we “really” are.

This study shows two extremes regarding the idea of imposture in general:

- The real imposture, or a person deliberately hiding the truth in order to actively deceive others, to serve his (or her) own goals without caring about the consequences. This is not what we mean by “imposter syndrome”.

- The Neurotic imposture, a strong subjective experience of fraudulence. The person feels unauthentic despite all the good results and praises.

The characteristics of the second point (what we call imposter syndrome) are very similar to Clance’s characteristics we saw above.

What Causes the Imposter Syndrome?

Now that we’ve defined precisely what’s the problem, we can now try to understand where it comes from.

The Family Environment

We’re coming back to the social expectations for this one. Many scenarios are possible to explain Davina strong imposter syndromes, but here are some hypotheses:

- Davina wasn’t considered intelligent enough. Difficult to believe the praises and good results when you’ve been taught at a young age that you’re not capable of such achievements.

- Davina was considered too intelligent. To avoid deceiving her relatives, she always had to be the best, or at least pretending it. As a result, the image she has of herself and the one perceived by the others feel different.

- For Davina’s family, success require little efforts if you’re intelligent enough. As such, hard work shows a lack of skill and shouldn’t bring praises and positive results, even if they come to her.

- Lack of positive reinforcement: when Davina was working hard, only the result was praised, not the fact that she worked hard.

- Davina was praised to have good social skills. Therefore, she explains her success by her abilities to shine in society, not because she was intelligent or skilled.

That being said, many studies found out that the total contribution of the family in the development of the imposter syndrome was pretty low. According to the conclusions given by the Freakonomics, the child’s environment (friends, school) is more influential than the family itself. Maybe this is where we could get some answers?

Unfortunately and too often, the school system only reward the results, not the effort. It teaches us that it’s not good to fail, possibly creating the fear of failure. Personally, I think teachers can have a strong influence on a child; I know for sure mine had.

I also strongly believe that without failures, success will be scarce. It’s easier not to fail and directly cross the path of success; but it’s rarer, especially if the success is difficult to reach.

But here’s the problem: we’ve been conditioned, by many forces around us, to think that we shouldn’t fail. It’s very difficult to reverse this kind of influence; we’ll come back to that.

Our Personality

It becomes clear, looking at the studies, that the imposter syndrome can be correlated with poor mental health. Neuroticism (having often negative feelings, mood swings, sign of depression, and high anxiety) is strongly correlated with the imposter syndrome.

We spoke about perfectionism before, but it’s an important characteristic of the imposter syndrome. What are the possible causes? For Davina, it could be:

- Having excessively high and unrealistic goals, as we saw above.

- Generalizing over a single failure: thinking that her whole month, year, or life, was only failures.

- She wants to appear competent, special, or even perfect for herself and the others.

Don’t get me wrong: you can be a perfectionist without experiencing the imposter syndrome. A perfectionist won’t necessarily speak about their mistakes because of the fear of being imperfect. On the other side, perfectionists with the imposter syndrome will often openly communicate about their mistakes, trying to hide behind them not to deceive the others even more.

It’s not clear if the imposter syndrome is more a fear about social expectations (what the others will think about us) or if it’s more about the image we have of ourselves. In my experience, it’s both.

Can Everybody Be Victim of the Imposter Syndrome?

According to this recent study, everybody can experience the imposter syndrome, whatever the age, gender, level of education, atmospheric pressure, or favorite Pokémon. The data is staggering: around 70% of people will experience at least one episode of imposter syndrome in their life.

Still, individuals experiencing it will often have a strong feeling of loneliness. After all, few of us speak about it. We don’t share our personal experiences related to these feelings. More on that later.

The Consequences of the Imposter Syndrome

Success should contribute to Davina’s happiness: after all, she’s doing a good work, contributing to society, moving forward to her goal, chasing her higher purposes. But more she walks along the imposter road, more her success have a bitter taste. She becomes more and more uncomfortable with her achievements.

Here are the possible consequences of spending too much time spend on the imposter road:

- Burnout.

- Anxiety.

- Emotional exhaustion.

- Decrease in job performance and poor achievements (overworking is not good for the quality of your work).

- Decrease in job satisfaction.

- Loss of motivation.

- Sense of guilt and shame about success.

- Depression.

Don’t let yourself reach these extremes.

How to Overcome the Imposter Syndrome?

I won’t lie: there’s no quick solutions to “solve” the imposter syndrome. According to some study we saw earlier, it could even be a normal consequence of our social life.

But it doesn’t mean that these feelings need to be strong or regular. First and foremost, you’ll need the will to change your way of thinking, to try to fix some of your thinking habits day after day. I believe that patience and determination are the keys here.

Where Are You on the Imposter Road?

It might be useful for you to first assess how strong your imposter syndrome is. Try to listen to yourself first, but it can be very difficult to assess our feelings.

Over the years, some tests were developed to find out how strong the imposter syndrome is for somebody. The most famous is the Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale (CIPS); unfortunately, I couldn’t find any other on the Great Internet (like the Harvey’s IP test).

If you have access to any other test measuring the imposter syndrome, don’t hesitate to post the link in the comment.

For the curious, at the time I’m writing this article, my personal best is 74. It only confirmed what I experienced: I often have imposter feelings.

For anybody having a high score: welcome abroad! For the others, I hope it won’t get higher. For everybody: let’s try to decrease it.

Personally, I plan to do this test from time to time to see if there are any improvements. We need to keep our mental health in check.

Seek The Support From the Ones You Trust

Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes, in their first paper about the imposter syndrome, found that it was very difficult to decrease these feelings with one-to-one therapies. The imposter syndrome is often too strong; it’s difficult to convince anybody they are not a fraud if they believed it for years. Only a few speak about it: showing our weaknesses, as we already saw, is not always considered as “socially accepted”.

That being said, they found as well that group therapies with others who have similar feelings can have good results. The feeling of loneliness is often strong when we’re victim of the imposter syndrome: it’s reassuring to see that we’re not the only one, and it enables us to speak about it.

So take your Twitter, your Facebook, your Instagram, your MySpace, your PDA, your Minitel, or just write a comment to this article, and tells the world that you’re a human. That you’ve weaknesses. That you’re not perfect. That you’ve experienced the imposter syndrome. Share your own story. Who knows? It might improve the life of an unknown person, somewhere in the world, who needed to read it.

Speak about your feelings to your close relatives: your family or your friends. I think it’s better to do that face to face, but your friends on Internet can help you as well, especially if you’re in the middle of a pandemic. Any bit of support count!

Changing Your Thinking Habits

If you often think that you won’t succeed the task which is given to you, you need to revert this habit of thinking. Like any habit, you need to:

- Be aware of it. Try to understand what you’re thinking when you have (or you want) to do something you could fail.

- Tell yourself that you’ll succeed when you think that you’ll fail. You could say it out loud, or even write it. It can make the statement more real (and therefore more powerful).

- Try to notice when you’ve got a great success without having any prior self-doubt. This is a great achievement by itself! If your self-doubts were a bit less strong than before, it’s awesome too.

It might sound easy (or even cheesy), but it’s not. It’s difficult to be aware of our thoughts and feelings. Personally, meditation is the only activity which helps me look at what I have in my head. It can be hard to practice (even if it looks simple), but you’ll learn a lot along the way.

Keeping Record of Positive Feedback

Another solution proposed by Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes: keeping a record of the positive feedback you’ve received. It’s easy to distort the praises we get. Writing them won’t let your mind transforming them to fit your inner narrative.

Writing for me is very therapeutic. It can create a great awareness and can help you to move forward. It won’t be the case for everybody; but it doesn’t cost anything to experiment for yourself.

Involvement and Acceptance

This one is a personal one, not really based on any study. I believe that fighting the imposter syndrome is not necessarily a good idea. Fighting sounds like a destructive and painful process. Instead, I’ve got better results by trying to accept my feelings and my thoughts, and trying to gently change them. Letting them pass without them poisoning my life works too.

This is a difficult exercise, but gaining a minimum of control on our feeling is priceless. It doesn’t mean that we become robot, unable to have any feeling at all. It means that we can sort out our feelings from a distance. We can then allows the positive ones to flourish while discarding the negative ones.

Again, meditation is the only method I found to do exactly that. If you have any other personal solution to achieve this kind of awareness, please tell us how. You know, the comment section, yadi yada.

We saw earlier, according to most studies, that the age of a person is not a deciding factor for the imposter syndrome. That being said, this study found that people from 45 to 60 years old experience less these feelings than younger ones. Why?

- They have other priorities than their work: their families, for example.

- They have less energy to give in their work.

- They accept the company culture more than younger people, and they don’t try to change it anymore.

- They communicate more effectively and are less likely to have long and tiresome debates.

This shows an important point which comes back in many studies: the more you’re involved in your work, the more you’ll experience the imposter syndrome.

As developers, we’re often passionate about what we’re doing, putting our souls in our work. Here’s my advice: that’s great, but don’t put too much. Always keep yourself and your health in check as much as possible. If you manage a team, try to keep that in mind for your team members, too. Our health and the health of the others are the most important.

Company Culture

This is again from my personal experience, as well as from the excellent book Accelerate. Some companies have a culture which has one or more of these properties:

- Power oriented: managers are always right.

- Information withhold or distorted on purpose, often for personal gains.

- A lot of politics, threats, blames, and fear.

This kind of company culture can break anybody. Burnout and the imposter syndrome (this time because you’ll have the impress that you’re never good enough) will rise very quickly in these toxic environments.

As Gandalf was saying so eloquently: fly, you fools. In common tongue: find another job.

If you don’t have the choice and you need to stay in your soul-crushing company, work toward having the choice. Meanwhile, accept that your company is sick, and try to create mental barriers to be as less involved as possible. Don’t think you’re responsible: you’re not.

Now, here’s an idea I learned the hard way: people don’t like to change. If you think you can improve your company by changing its way of working, or by changing the way some of your managers are behaving, you’re likely to fail. It doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t try, but be aware of the difficulty.

If you’re a developer and you’re only seen by your managers as a mean to enable their dreams of money and fame, you won’t have much impact. This is sometimes not directly visible when you begin to work for these gulags, unfortunately. Keep an eye open and don’t spend all your mental energy in a lost cause.

The Imposter Syndrome in the Software industry

The Valuable Developer is, as the title implies, a blog for developers, so let’s speak about the software industry more specifically. Again, this part is from my personal experience; nothing scientific here (as far as I know).

An Ego Driven Field

On one side, IT is an ego-driven field. Some developers out there will affirm their positions strongly, thinking they are right and the others are wrong. Some seem to think that they always have the perfect solution, or that everything is easy and it doesn’t take time.

On the other side, many of us experiment the imposter syndromes. It looks contradictory: how can we be ego monsters if we see ourselves as fraud?

I believe that these ego-driven behaviors come to the fact that we’re insecure: whatever we’re doing, the software entropy will increase, we’ll have bugs, we’ll have to manage greater and greater complexity.

So we try to hide, to higher our voices, to show that we know what we’re doing, even if we don’t. You know what? That’s fine not knowing. Let’s stop pushing ourselves down, and let’s accept that we’re working in a very young industry which doesn’t have many empirical answers. It’s better than throwing half-baked beliefs to each other while affirming it’s the Only Truth™.

Useless Competition

Our industry is very competitive too. Did you hear (or read) the following affirmations before?

- “If you don’t know X, you’re not a Senior, a Junior, or even a ‘real’ developer”.

- “A 10x developer does this or that better than anybody else (including you)”.

- “A senior developer should know that! How don’t you know it?”.

- “Davina is a mediocre developer, look what she did in the codebase yesterday!”

We’re competing via:

- Tests given during technical interviews (often dictating the salary you’ll end up with).

- Platforms like HackerRank.

- Hackathons and various other ways for companies to get some work done for free.

This isn’t healthy or even useful. Coding is a mean to an end, not the end itself. If you’re working on the wrong product, a perfect codebase won’t make it good. If you don’t understand the business context you’re in, your codebase will stink. Should we focus on that, instead on focusing on these petty competitions?

My goal is to help the companies I’m working with. It’s not to have medals, stars, and other ridiculous “rewards”. It’s not to have the gruesome title “Ninja Developer”. It’s not to grind “cracking the coding interview” and this whole literature which understood that, even if many are talented developer in practice, it’s not enough to pass these tests.

Still, this competition can give you a very wrong image about yourself and your worth.

Here’s my advice: always compare yourself to your past self. Try to accept praises as they are, without thinking that you’ve deceived or even manipulated the other party. If you think you did, try to stay aware of it as much as possible and stop yourself doing so.

Look at your past experiences and keep in mind the positive impact you had on the companies you worked with, and on your peers. Do it regularly. These are real, and your inner voices affirming the contrary are wrong.

The Value of Intelligence

I would conclude this part with something I always found alarming in our industry, and in our society in general: our perception of intelligence.

Scientists can’t really define what’s intelligence precisely, still we spend our time judging each others based on this blurry concept. Everybody can have his (or her) own beliefs about it: for some it will be more about the capacity to adapt and learn, for others it’s the amount of knowledge one has. In short: everybody has different beliefs.

Now, a question: how many times did you hear the following?

- “This person X is very intelligent”

- “That’s very smart what you did”

- “That’s not smart at all!”

My answer: too often.

Considering intelligence as the Holy Grail which decides alone of our worth messes up with our mental health big time. What about focusing on others properties, more realistic ones, like the concrete consequences of our actions? What about trying to describe the thinking processes which lead us to nice solutions? To me, it sounds more useful than simply declaring: “oh! It’s very smart!” and walking away.

Is the Software Industry That Bad?

The software industry I describe here looks pretty awful; it’s not. Many developers love to share their knowledge and help as much as they can, via blogs, conferences, great communities, or simply by mentoring beginners in their companies. We develop countless of open source software to help our peers. Even if we face some problems, like any industry, I still think that many aspects of it is awesome.

You’re Worth It

I’ve begun this story with the failures I’ve had in different interviews to find a job, but the problem was deeper.

I was walking on the imposter road for months, maybe even years. I feel better now, trying to be conscious of my worth in a more precise way, trying to appreciate what I brought to the companies I worked with, to the industry as a whole, and to any person who read these lines. On the other side, I try to pinpoint where I need to improve, in what context, trying hard to listen to the others.

In short, I’m trying to keep an accurate mental model of myself in order to improve. Easier said than done, but if we choose the good road, everything else gets automatically better.

Enough rambling about me. What did we learn in this article?

- The imposter cycle is an infinite loop where you’ll have bumps of satisfaction followed by anxiety and doubts, making any success bitter.

- The fear of failure (or the fear of success) can stop you for thriving in what you love doing. Try not comparing yourself to the others and be proud in what you achieved.

- If you want to be the best, you won’t make it. There is always somebody who seems better than us; instead, try to do your best, your way. Pinpoint your mistakes, and try to improve from there.

- True humility is a good quality. But humility doesn’t mean undermining our successes and the praises we receive. Having an accurate perception of our worth is important too.

- It’s not clear where the imposter syndrome comes from, but our conception and high praise of intelligence doesn’t help us (or our peers) to have a good mental model of ourselves.

- Being on the imposter road for too long will undermine your mental health. Remember: health is the most important.

- We need to speak more about our own experiences regarding the imposter syndrome, to support each others. To tell the world that it’s fine to have these feelings.

- If you’re experiencing the imposter syndrome, you’re not alone. Speak about it with the persons you trust the most, the ones who can support you.

- I believe that the IT industry is a competitive mess where many of us claim knowing everything, even if we’re full of doubts and insecurities. The focus should be on what we’re building and how to make our users happy, not infinite debates which don’t improve anything.

There is no imposter syndrome without involvement. In that sense, experiencing it also proves that we love what we’re doing, that we want to improve, and, as a result, that we are more than likely to have a positive impact, whatever our inner voice is telling us.

Always keep in mind this simple fact before blaming anybody, including yourself.